HOW TO STOP EXTINCTION

Endangered Species day is dedicated to spreading awareness about the 37,400 species around the world that are threatened with extinction. That is a shocking 28% of all species that have so far been assessed by scientists. As our unsustainable hunger for Earth’s resources continues, this list will get longer. But it’s not too late. Together we can fight back and help save life on Earth. Read about how we can all do more to re-wild our planet and save biodiversity, not just today, but every day.

African Painted Wolf. Endangered (EN). Less than 500 remain in South Africa.

“Unless humanity learns a great deal more about global biodiversity and moves to protect it, we will soon lose most of the species comprising life on Earth”

Today, many species we love are on the verge of extinction (and the not-so-loved ones too). The list is long and sad, from the most well-known cases sitting on the very edge of survival, to those you haven’t heard of yet. Did you know that one of the most threatened species on Earth is right here in the United States, the Red Wolf, with less than 18 surviving in the wild. There are many more species in trouble than we yet know, from amphibians, to fungi and fireflies. And the ones that we know well are in trouble too. They fill the pages of storybooks we give to our children: the beloved elephant, rhino, giraffe, lions and the biggest blue whales. Countless others slip through the cracks before they are even discovered.

“In short, we live on a little-known planet. E.T. and other alien biologists visiting Earth would, I suspect, be appalled at our weak knowledge of our homeland. They would be mystified by the scant attention humanity gives to the life-forms on which our existence depends.”

For many of us growing up, the poster child of extinction was the Dodo and the Tasmanian tiger. Today, the list of animals imminently headed in the same direction is overwhelming and heartbreaking. The population numbers for these critically-endangered species is truly a code-blue emergency requiring immediate and urgent intervention. Examples include:

The Malayan tiger (Panthera tigris jacksoni): estimated population between 250-340 (Malaysia)

The Red Wolf (Canis rufus): 18 remaining in wild (USA)

The Amur Leopard (Panthera pardus orientalis): only 50-57 individuals (Russia)

The Vaquita Porpoise (Phocoeana sinus): as few as 10 (Mexico)

The African Forest Elephant (Loxodonta cyclosis): news this year that they have lost 86% of their population in just one generation (Central Africa)

The Northern White Rhino (Ceratotherium simum cottoni): 2 (Kenya)

Everything is connected. It’s not just the loss of an individual species that is devastating. Pulling and removing a thread from the web of life has system-wide consequences, and causes the health of ecosystems to unravel. The more complex, the more diverse an ecosystem, the healthier and more resilient it is. The opposite also holds true - when native species disappear, the ecosystem becomes unbalanced and a connected string of changes are unleashed. Disease can take hold. New viruses can emerge. Rivers change course. Grasslands turn into bush. Additional species that depended almost entirely on the lost species will also disappear. These adaptions and the interlinked relationships between soil, insects, plants, animals, birds and the climate have taken millions of years (literally) to evolve. Life on earth simply can’t adapt as quickly as the changes and pressures we are placing upon it. As we pull at the fragile threads of ecosystems, the losses cascade.

A herd of critically endangered forest elephants digging for mineral-rich mud to supplement their diet. Photo Credit: Martin Harvey/Wildscreen Exchange.

Take elephants as an example. Where elephants disappear, they leave a big gap — not just physically, but also as ‘ecosystem engineers’. Some tree species depend entirely on African forest elephants to eat their fruits, swallow their large seeds and deposit them elsewhere in a pile of nutritious dung, important for dung beetles and other little insects. As they knock down trees and chew up huge amounts of plant material, both forest and savanna elephants change their environments in ways that create new habitat for other species. Even their footsteps create habitat: frogs breed in the shallow water-filled holes left in their big heavy tracks. By stomping down smaller trees, elephants promote the growth of large hardwood trees that absorb more carbon. Scientists estimate that if forest elephant disappear, Central Africa’s rain forest will lose about three billion tons of carbon — the equivalent of France’s total CO2 emissions for 27 years.

We can’t stand by and let them disappear.

So what can we do? How can we fight back against extinction and lend our voices, our talents and our determination to help the wild world, the millions of other species we share our planet with? First we have to focus on the big things so we can take action, and make it count. And we need to act fast.

What are driving the forces of extinction around the world? The science is clear: the number one driver is habitat loss: changes in land and sea use by humans. Whenever we take over natural areas for our own use, we are encroaching on and damaging or destroying the habitat of other species. We are doing this at an alarming rate. 50% of habitable land on Earth has been destroyed for agriculture, with 90% for animal agriculture. We have taken over the planet, and we are taking up the last wild spaces, crowding out the space needed for biodiversity, the millions of other species we share our planet with, to survive.

Wild Tomorrow Fund’s Ukuwela Reserve on the left, saved from a fate that would have turned into an expansion of the pineapple field to the right.

The main direct drivers of land degradation and associated biodiversity loss are:

Expansion of crop and grazing lands into native vegetation

Unsustainable agricultural and forestry practices

Climate change, and, in specific areas

Urban expansion, infrastructure development and extractive industry.

What is the solution to habitat loss, so we can push back against this leading force driving extinction?

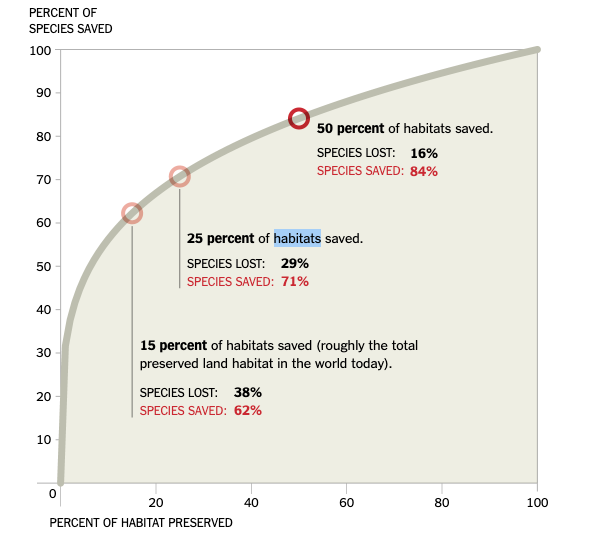

In E.O. Wilson’s call for action, Half Earth (2015), he sets out an ambitious yet simple solution: we must save 50% of land and ocean to save 80% of species on our planet. His scientific calculations show that a full representation of the Earth’s principal habitats and the vast majority of its species can be saved within half the planet’s surface. “At one-half and above, life on Earth enters the safe zone. Within half, existing ecosystems indicate that more than 80% of the species would be stabilized.” And if we can’t meet these targets, species will continue to be lost.

Source: The New York Times, 12 March 2016. Op-ed by EO Wilson, The Global Solution to Extinction.

This shows us that we have a window of opportunity. We have the solution. We can save life on Earth if we can set aside the largest reserves possible for nature in strategic places home to the highest densities of biodiversity (biodiversity hotspots and key biodiversity areas are examples of how to measure this). These areas will then be able to protect higher levels for biodiversity if they are linked together with corridors, and for habitat that is already degraded, restored. “Even though extinction rates are soaring, a great deal of Earth’s biodiversity can still be saved” says EO Wilson who like a compass, guides our vision. We must re-wild our planet.

Today we are far from the Half Earth Goal. Only 15.7% of Earth’s land surface and 7.7% of the ocean is under conservation protection. It varies from place to place (check out the protected planet database): New York State is at 20%. Costa Rica has designated almost 28% of its land area as protected. South Africa is sitting at only 8% protected. But we can get there, step by step, acre by acre. Firstly we must minimize our harm by halting any more destruction of wild lands, particularly in places home to high levels of threatened biodiversity. That is what we were able to do by saving the Ukuwela Reserve in South Africa. The 1,250 acres now under our protection were at immediate risk of conversion to monoculture pineapple farming. We stopped this destruction by purchasing the land instead of the farmers. We are now formally protecting this land for biodiversity conservation. This will proudly contribute to the region, South Africa’s and the world’s protected area goals. Together we can protect and restore wild lands. This is what it takes to save species from extinction.

There is a global movement aligning towards this goal. The Global Deal for Nature is calling for countries to double their protected zones to 30% of the Earth’s land area, and add 20% more as climate stabilization areas, for a total of 50% of all land kept in a natural state. The 30 by 30 plan is a goal of the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity to get the world well on the way to Half Earth by 2030. It’s a growing movement. Yet still, less than 3% of US philanthropic giving is for the environment. We need to give Nature and our planet more support. It is in our best interest - it’s our life support system.

“‘How is it possible that the most intellectual creature to ever walk on this planet is destroying its only home?’ ”

According to the IPBES Global Assessment (2018), a UN report compiled by thousands of experts on biodiversity and ecosystem services, “high consumption lifestyles in developed countries, coupled with rising consumption in developing and emerging economies are the dominant factors driving land degradation.” At the individual level we all have to work harder, especially in developed countries, to reduce our consumption. This thirst for nature’s resources comes at a deep cost to the planet and far-away places. It is our global hunger for example for pineapples, that is driving the expansion of deforestation in our region of KwaZulu-Natal. And our hunger for paper that converts wild lands nearby into paper plantations. It is our hunger for animal agriculture that drives the vast majority of deforestation. Every corner of the planet, the story is the same if we choose to look. So let’s make a change and reset our relationship with Nature.

Fighting back against the extinction of wildlife is why we started Wild Tomorrow Fund in 2015. For us, every day is endangered species day. We are fighting back against the forces of extinction by first saving and protecting ecologically important habitat, then restoring it. We are reconnecting the web of life in these threatened ecosystems acre by acre. It’s re-wilding in action. This is the most impactful conservation action we can take, backed by science, to save species.

We hope you will join us today and every day to fight back on behalf of wildlife and the full amazing spectrum of life on earth, biodiversity.

“Humanity is waging a war on nature. This is suicidal. Making peace with nature is the defining task of the 21st century. It must be the top, top priority of everyone, everywhere.”

REFERENCES

E. Dinerstein, et al (2019). A Global Deal For Nature: Guiding principles, milestones, and targets. SCIENCE ADVANCES19 APR 2019 : EAAW2869

Gutteres A. State of the planet. Presented at the UN Secretary General’s address, New York, NY, 2 December 2020. https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/un-secretary-general-speaks-state-planet

New York Times, 25 March 2021. Some Elephants in Africa are Just a Step from Extinction. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/25/science/elephants-africa-endangered.html

New York Times, 19 August 2019. The Thick Gray Line: Forest Elephants Defend Against Climate Change. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/19/science/elephants-climate-change.html

New York Times, 12 March 2016. EO Wilson. Op-Ed: The Global Solution to Extinction. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/13/opinion/sunday/the-global-solution-to-extinction.html

IPBES (2018): Summary for policymakers of the assessment report on land degradation and restoration of the Intergovernmental SciencePolicy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. R. Scholes, L. Montanarella, A. Brainich, N. Barger, B. ten Brink, M. Cantele, B. Erasmus, J. Fisher, T. Gardner, T. G. Holland, F. Kohler, J. S. Kotiaho, G. Von Maltitz, G. Nangendo, R. Pandit, J. Parrotta, M. D. Potts, S. Prince, M. Sankaran and L. Willemen (eds.). IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany. 44 pages.

IPBES (2018): The IPBES regional assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services for Africa. Archer, E. Dziba, L., Mulongoy, K. J., Maoela, M. A., and Walters, M. (eds.). Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Bonn, Germany. 492 pages. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3236178

IPBES (2018): Summary for policymakers of the assessment report on land degradation and restoration of the Intergovernmental Science Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. R. Scholes, L. Montanarella, A. Brainich, N. Barger, B. ten Brink, M. Cantele, B. Erasmus, J. Fisher, T. Gardner, T. G. Holland, F. Kohler, J. S. Kotiaho, G. Von Maltitz, G. Nangendo, R. Pandit, J. Parrotta, M. D. Potts, S. Prince, M. Sankaran and L. Willemen (eds.). IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany. 44 pages. Available online here.

World Bank. World Database on Protected Areas ( WDPA). Available here.